C’est avec

une régularité comparable – mais tous les deux ans

seulement – à celle que montre le trio en prenant la route,

chaque hiver, pour une tournée en forme de Winterreise (disque

psi), que nous parvient un nouveau bulletin de l’excellente santé

musicale du groupe, fondé il y a près de quarante ans.

Cet enregistrement de novembre dernier, qui entre en résonance

avec tout un corpus phonographique, a été saisi en concert

à Dessau : il offre une longue improvisation de quarante minutes,

prolongée de deux pièces plus brèves, et fait en

quelque sorte pendant aux dix instantanés du précédent

disque (Gold Is Where You Find It), gravé en studio, courant

2007 – tout comme il y a vingt ans, chez FMP, Physics répondait

à sa manière aux Elf Bagatellen…

D’une compacité et d’un raffinement toujours aussi

étonnants, l’agrégation d’Alexander von Schlippenbach

(piano), Evan Parker (au seul saxophone ténor) et Paul Lovens

(batterie) déploie ses mondes en une variation infinie que l’auditeur

suit avec d’autant plus de plaisir que cette continuation, cette

«version», cette reprise du matériau fait remonter

de véritables pépites… Si les efficaces principes

de l’économie intime du trio – énergie au

combustible rythmique, rouleaux pianistiques en guise de paliers (redistribution,

entrées, bifurcations), constructions klangfarbentes jamais barbantes

– sont connus, la musique n’en est pas moins merveilleusement

malaxée et tannée, délicatement hirsute et poétique

: une houle de très grande classe !.

Guillaume Tarche, Le son du grisli, France, Juni 2010

*

* * * (4 stars)

German pianist Alexander

von Schlippenbach's free-improvising trio, with percussion Paul Lovens

and British saxophonist Evan Parker, has been around on and off for

a remarkable 40 years. This set was recorded at the Bauhaus –

a point made much of in the liner notes, showing how Bauhaus theories

on space, enclosure, beginnings and endings chime with free-improv's

narrative-disrupting methods. But it's inevitable that such a long-running

partnership should develop its own personal narrative, and there are

passages in these three long tracks in which the players banter and

echo phrases as knowingly as any regular jazzers, or even offer a kind

of distorting mirror to conventional pulses and grooves. Parker plays

tenor sax throughout. He's gruffly lyrical at the opening but soon opens

out into his characteristic jagged runs, gutturally swerving around

Lovens's clanging cymbals and Schlippenbach's Cecil Tayloresque torrents,

before evaporating into soft multiphonics toward the end of the 40-minute

opener. The second track develops an eerily Latin groove, while on the

third, dreamy, ballad-like swoops over cymbal-edge sounds and soft piano

undulations turn stormy and then reflective again. It might be a little

grizzled now, but one of the great free-jazz ensembles still throbs

with life.

John Fordham, The

Guardian, London, July 16, 2010

Pirmin

Bossart, Kulturtipp, Zürich, 31. Juli 2010

Jazz-CD-Tipp

Der freie Fluss kollektiver Ideen

Neue CD „Bauhaus Dessau“ vom Alexander von Schlippenbach

Trio

Das Dessauer Bauhaus begeisterte nicht zuletzt Arnold Schönberg,

sah er doch in diesem funktionalen Interieur ideale Voraussetzungen

für befreites künstlerisches Schaffen gegeben. Fast ein Jahrhundert

später fühlt sich das Trio um den Freejazz-Pionier Alexander

von Schlippenbach nicht minder inspiriert durch dieses Ambiente - der

Konzertaula mit ihren Stahlrohrmöbeln, aber auch den weiten Glasflächen,

die den unverstellten Blick und den freien Fluss der Energien begünstigen.

„Bauhaus Parts 1-3“ nennt sich der aktuelle Mitschnitt einer

Kollektivimprovisation von Schlippenbachs Trio. Und es hat Referenzcharakter,

wie Pianist Alexander von Schlippenbach, Evan Parker am Saxofon und

der Schlagzeuger Paul Lovens hier demonstrieren, dass sie scheinbar

seit Menschengedenken in bester Intuition aufeinander eingeschworen

sind. Spontan und assoziativ kommt ein improvisatorischer Fluss in Fahrt,

der vor kommunikativer Gewitztheit, Reibung, ja Humor und schier grenzenlosen

dramaturgischen Kontrasten nur so sprüht. Wo, wie hier, in diesem

idealtypisch freien Musizieren jede formale Festlegung überwunden

scheint, entfalten sich unmittelbare Ideen und klanglicher Raffinesse

umso direkter. Schlippenbach traktiert die Tasten und bringt Klangmassen

zum Leuchten, Schlagzeuger Paul Lovens antwortet mit seiner ganz individuellen

Geräuschwelt und oft unfassbar schnell – nicht selten Note

gegen Note setzend. Das hat Klasse, legt Prägungen offen, verrät

Spurenelemente. Schlippenbach, der bei Bernd Alois Zimmermann studierte,

leugnet seine Affinität zur Zwölftonmusik nicht. Evan Parkers

expressives Saxofonspiel bringt –natürlich!- auch coltraneske

Elemente ins Spiel. Das alles bündelt sich in diesen energiegeladenen

62, 57 Minuten – und braucht dafür keine Sekunde mehr. Denn

improvisieren heißt, den Moment zu feiern.

Stefan Pieper,

Recklinghäuser Zeitung, 6. August 2010 und

www.ruhrbarone.de

Ulrich

Steinmetzger, Thüringischen Landeszeitung, Deutschland, 14. August

2010

The Schlippenbach Trio is

now decades old; perhaps it's not surprising there are only a few improvised

music groups that have lasted that long. In this trio's case the matter

of pedigree goes without saying, but whether or not the depth of their

familiarity with each others' work makes for sterile, unrewarding music,

is a question that easily comes to mind.

On this occasion it isn't, as it's far from sterile and unrewarding.

Evan Parker, in particular, is responsible for this outcome. He plays

tenor sax exclusively, and it's clear that his vocabulary on the horn

is in a state of flux. This is hardly surprising, given the degree to

which he's worked the music's farthest reaches throughout his career.

When this music was caught for posterity in November of 2009, his work

demonstrated the hallmark of opening out and perhaps embracing the work

of Lou Gare or Fred Anderson in its linear flow. Having said that, Parker's

use of silence on the lengthy "Bauhaus 1"—a product

more, perhaps, of premeditated deployment rather than length of breath—has

the effect of giving the music some in-the-moment structure, even when

his band mates are opening up and giving vent to torrents of ideas.

Pianist Alexander Von Schlippenbach's approach to the piano is not so

much more measured, by comparison with his earlier work. as it is the

result of him listening more overtly. This is apparent by the time the

tenth minute of the piece rolls around, where the pianist and and drummer

Paul Lovens are fashioning music out of small sounds. Parker, ever alert

to the implications of the moment, accordingly lays back—insofar

as such a description is applicable to music of this strain. The music

is brooding some 22 minutes in, however; but this is as much the product

of the deep listening that can be taken for granted with musicians like

these as it is anything else.

It can also be taken for granted that "Bauhaus 2" and "Bauhaus

3" are more than mere afterthoughts for all their comparative brevity.

The dialogue between Schlippenbach and Lovens, in the opening of the

first of these, is a summary of their abiding knowledge of each other's

music, while it's notable that in the lower reaches of the tenor sax's

range Parker is ruminative and, if anything, even more conscious of

space. That strain is more apparent on the latter, where the music's

irresolution seems guided by a single mind.

Nic Jones, www.allaboutjazz.com,

USA, August 15, 2010

Thomas

Hein, Concerto, Österreich, August / September 2010

Edwin

Pouncey, Jazzwise, Great Britain, September 2010

Harri

Uusitorppa, Helsingin Sanomat, Finnland, 14. Elokuuta 2010

Andy

Hamilton, The Wire, Great Britain, September 2010

Verfluchte Jubiläen,

Gedenktage und -jahre, ich weiß selber, dass die Zeit vergeht.

Nun also 90 Jahre Bauhaus und 40 Jahre SCHLIPPENBACH TRIO = Bauhaus

Dessau (Intakt CD 183). Der Mitschnitt entstand tatsächlich 2009

im Bauhaus Dessau, 9 Jahrzehnte nachdem Walter Gropius diese Kunstschule

gründete. Nur, wo ist der Grund zu feiern? Die DDR wurde verplattenbauhaust,

dass man nach Pruitt-Igoe-Sprengstoff schreien möchte, die BRD

im 'Internationalen Stil' betoniert mit den Idealen von Möchtegern-Le-Corbusiers.

Und anschließend in den fetten Jahren übertürmt mit

Orthancs im SOM-Design. Kubische Form, radikaler Funktionalismus, blanke

Materialästhetik, billiger Wohnraum, getürmtes Kapital, jeder

Transparenz und jedem Menschenmaß zum Spott. Planten nur die Falschen,

oder wurden die Bauhausideen falsch angewandt? Stecken in sozialen Brennpunkten

und Sanierungsfällen gute Absichten und ein arkadischer Traum?

Gropiusstadt, mon amour? Egal, Alexander von Schlippenbach, Evan Parker

und Paul Lovens sind natürlich die richtigen alten Dessauer, Vertreter

einer tatsächlichen RaumZeit-Revolution, näher bei Kandinskys

und Schönbergs Gelbem Klang und den Farben zwischen den Farben,

den Tönen zwischen den Tönen, als bei Schwarz, Weiß

und Zementgrau. Ich käme nicht auf die Idee, ihre Konstruktionen

als transparent zu bezeichen, im Gegenteil. Aber dass in dieser 'aufgetauten

Architektur' (wenn man Schopenhauers Spruch umkehrt) die diagonalen,

transversalen und vertikalen Vektoren und neue Materialien dominieren,

um, entsprechend Gropius' Diktum, die 'Erdenschwere schwebend zu überwinden',

das ja. Allerdings kein Schweben, ohne eine dynamische, tripolare, elastische

Zentrifugalität, die ständig Energie zuführt. Schwebende

Momente sind selten, aber es gibt sie auch - etwa in Schlippenbachs

Geperle, Lovens Tickeln, Dongen und Rasseln und Parkers luftigem Tenorhauch

als langem Ausklang des großen 'Bauhaus 1'-Blocks von 41 Min.,

dem ein 12-min. zweiter und ein, diesmal gleich anfangs schwebzarter,

9-min. dritter folgen. Parker spielt ausschließlich Tenor, knatternd,

druckvoll, molekular, aber doch 'sand- und zementhaltiger' als seine

typischeren Sopranobestrahlungen. Alles in Allem sollten die Bauhaus-Bezüge

aber nicht die heterogenen und ikonoklastischen Stärken des Trios

überbauen.

Rigobert

Dittmann, Bad Alchemy Magazin 67, Deutschland, Herbst 2010

Reiner

Kobe, Jazz n' More, Schweiz, September / Oktober 2010

G.B.,

Inrocks Magazine, France, Autumn 2010

These jazz and improvisation

pioneers have performed together within various ensembles as leaders

and members of numerous band aggregations for decades. Yet, pianist

Alexander Von Schlippenbach’s Trio has triumphantly withstood

the sands of time, spanning four decades. And the artists intuitive

performances are in alignment with the stars, here on this comprehensive

outing captured live in Bauhaus Dessau, Germany.

The trio’s acutely visualized artistic craftsmanship parallels

Germany’s legendary Bauhaus art school, founded in 1919 via multi-phased

patterns, sharp trajectories and diametrically opposed choruses. On

this 2010 release Evan Parker performs solely on tenor sax, and drummer,

percussionist Paul Lovens helps synchronize or decompose the various

cadences with remarkable agility. In effect, Lovens lucidly demonstrates

his skills and for my money should be counted among the top-five or

so, improvisational drummers of all time.

Essentially, the trio bridges the gap between torrential downpours of

music, underscored by emotion and passionate colloquies. The musicians

execute ascending search and conquer missions, yet temper the flows

into deft frameworks, especially noticeable on the 41-minute opener,

“Bauhaus 1.” Sparked by whirlwind flurries and 360 degree

shifts in strategy the musicians inject budding cadenzas while mimicking

each other’s moves and intersecting ideas.

The trio prudently tempers the dynamic via meaningful exchanges that

mimic the human element. On “Bauhaus 3,” Parker and Von

Schlippenbach launch the events with warmly modeled choruses. Moreover,

Parker’s yearning notes chart a course for a metropolitan-like

hustle and bustle vibe, and they finalize the procedures with a whisper.

Hence, the audience’s rousing applause sums up and reinforces

the impressionable performance, although most advocates of this genre

would not foresee anything less from these consummate pros.

Glenn

Astarita, Jazzreviews, September 2010

Das Bauhaus … na klar,

eine Errungenschaft der Moderne und ebenso ihr Tempel, und wer schon

mal da war, den haut es erstmal um wegen der stringent-sinnigen Konzeption

und der lichten Umgebung. So hätte es werden können - die

Pläne sind gut, doch die Menschen sind schlecht. Bleibt die Kunst

als säkularisierte Religion: das Bauhaus als Ort materialisierter

Ästhetik, in der die Energien besser fließen - oder etwa

nicht? Ja, das Bauhaus … auch eine dieser schönen sicheren

handwarmen linken Ikonen, deren Ideal und Wirklichkeit stets aneinander

gemessen werden müssen. Trotzdem ein toller und sinniger Spielort

für das beste Freejazztrio der Gegenwart, das hier in drei Teilen

ein begeisterndes Zeugnis für den Geist, der stets vereint und

wieder sprengt, aus dem Moment heraus schafft. Es ist absolut großartig,

und ja, es ist Jazz. Kein 12Ton. Nein. Rahmen und Verbindung sollten

zu keiner Sekunde überstrapaziert werde. Es ist einfach nur grandios

im Jetzt. Und, verehrtes Publikum: diese Transgression wirkt zu keiner

Sekunde dekorativ. Und das ist wirklich sehr viel wert heute.

by

HONKER, MADE MY DAY, TERZ-Magazin, Deutschland, Oktober 2010

Angenommen, Frank Zappa hatte

mit dem Urteil recht, dass das Reden über Musik aussichtslos sei

und dem Versuch gleichkomme, zu Architektur zu tanzen. Dann könnten

wir in diesem Fall gleich zwei Aussichtslosigkeiten miteinander verknüpfen

und die Aufnahme des Schlippenbach Trios besprechen, das ein Konzert

in jenem Bauhaus Dessau dokumentiert, das unter der Leitung von Walter

Gropius bald einmal hundert Jahren zum internationalen Brennpunkt moderner

Architektur avancierte. Der Vergleich mag anmaßend klingen, aber

die Charakteristik des Schlippenbach Trios ist (auch wenn ich bisweilen

nicht durchblicke und das dann als Geheimniskrämerei missverstehe)

jener des Gropius-Baus in seiner überragenden Transparenz nicht

unähnlich. Die Transparenz der improvisierten Musik – und

das immerhin auch schon seit vier Jahrzehnten. Eine enorme Zeitspanne,

die allenfalls von einem Ensemble wie dem Arkestra übertroffen

werden kann, das aber outer space, jenseits von Raum und Zeit musiziert.

Dieser neuen Platte sind wieder alle Qualitätsmerkmale anzuhören,

die in ihrer Frische von Jahr zu Jahr noch erstaunlicher klingen: das

Zupacken und das Loslassen, die klaren Linien und die verschlungenen,

die Mathematik und die Poesie, die lange, nicht enden wollende Spirale

und das kurze Bonmot, die Überraschung und das Kalkül, die

Eleganz, die Nüchternheit – und die Transparenz. Womit wir

wieder am Anfang angelangt wären. Angenommen ...

felix,

Freistil 33, Österreich,

Oktober/November 2010

This live exhibition, recorded

November 2009 at Bauhaus Dessau, builds on the simple premise of celebrating

both the 90 years of Walter Gropius' creation and the fourth decade

of activity as a trio of Alexander Von Schlippenbach, Evan Parker and

Paul Lovens. This notwithstanding, there's absolutely nothing in the

music that could be exchanged for "official", if not plain

commemorative. Over the course of an abundant hour, three of the most

distinctive voices in the history of improvisation act without affectation,

exploring a broad range of dynamics and relations.

Among the trio's salient traits is the cutback of gratuitous flash in

creative prototypes devoid of placid anchorages. During the 42 minutes

of "Bauhaus 1", for instance, we find several moments of unquiet

interplay at the border between well-regulated agitation and rational

investigation of a resourceful interconnection. Parker — who articulates

visions exclusively through the tenor saxophone — is frequently

heard tightening the reins of his renowned cyclical blizzards, channeling

notes into structured spurts whose intermittence gives openings for

considerate insertions by Schlippenbach and Lovens. The latter's drumming

is, as always, equally vibrant and weighty in the overall economy of

the playing; occasionally, he seems to choose what to play based on

timbral principles rather than an ephemeral propulsive necessity. At

the end of the day, he's completely right.

And then, naturally, you have Schlippenbach. A pianism that runs the

expressive gamut with power, concentration, and grey-hued pensiveness:

the beginning of "Bauhaus 2" is permeated by this sense of

evaporating contentment, as if the musicians had suddenly decided to

go for bitter realism after sharing long stretches of inspired eagerness.

A total control on the mechanisms that police excessive virtuosity —

never prevailing upon the unadulterated flow of imagination —

is this sober master's specialty, one of the main reasons behind the

longevity of this unit and, accordingly, the symbolic extent of this

CD.

Massimo Ricci, The Squid's Ear, USA, 2010-09-29

Martin

Woltersdorf, Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, Deutschland, 17. September

2010

Bjarne

Soltoft , Jazznytt, Oslo, November 2010

Vierzig Jahre Schlippenbach-Trio;

Jubiläen, Feiern der Beständigkeit? Beständig lebendig

möchte man präzisieren, in diesem Falle zumindest. Drei unverkennbare

Individualisten, die seit nunmehr vier Jahrzehnten kontinuierlich gemeinsam

improvisieren, diese drei Pioniere des freien Spiels kennen einander

musikalisch bis ins kleinste Detail. Ihre Reaktionsgeschwindigkeiten

sind enorm, ihre Interaktionen pointiert und binnendifferenziert in

Klang, Dichte und Dynamik. Und diese dichten, längst nicht nur

oberflächlichen Verzahnungen sind es denn auch, die den spannungsgeladenen

Fluss dieser Musik ausmachen; nicht allein die meist dichte Energie

und Virtuosität, mit der die drei spielen: etwa Evan Parkers zirkular

geatmete Tongirlanden, Paul Lovens’ drängender, manchmal

Piruetten drehender Puls, mit dem er gelegentlich auch schon mal entferntere

Jazztraditionen streift, oder Alexander von Schlippenbachs sich aufbauende

Klang- und Motivarchitekturen.

Bauhaus, Dessau – hier entstand dieser Live-Mitschnitt. Und möchte

man nun, wie man es eben so tut, Verbindungslinien ziehen zwischen dieser

doch so dichten, eng verwobenen Mu sik und der Durchsichtigkeit und

Klarheit des Bauhauses, dann die, dass eben auch die Musik des Trios

in all seiner Energie äußerst klar und präzise improvisatorisch

konstruiert ist.

Nina Polaschegg, Zeitschrift für Neue Musik, Deutschland,

6, 2010

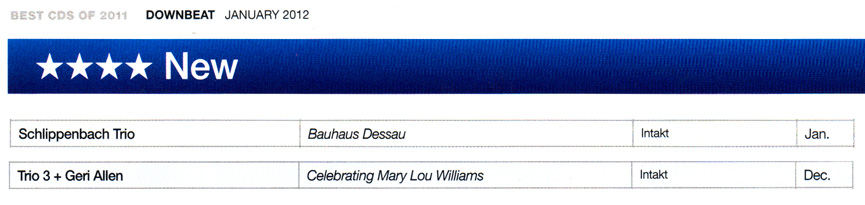

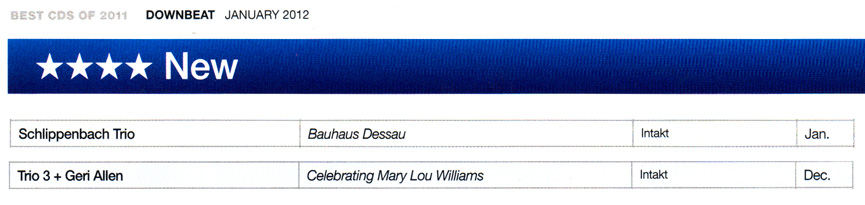

Peter

Margasak, Downbeat, USA, Jan 2011

The

trio of Evan Parker, Barry Guy and Paul Lytton has been around in some

form since at least the mid 1970s. They've released a slew of albums,

sometimes with various guests (Marilyn Crispell, Joe McPhee, Augusti

Fernandez, to name a few). And as good as things get with their various

guests, it's the trio's Free improvisational forays that seem the most

pure, almost classic (classical?) in their vision and sonic scope. All

three play beyond the extended range of their instruments. Parker's

upper register work, his endless serpentine lines and his extensive

vocabulary are second to none. Guy's massive technique and non-pareil

arco work map out a vast terrain in the lower sonic section. And

Lytton's pattering drum work and use of smaller percussive instruments

provide a rhythmic complement and adds a textural element that pushes

the music in a variety of directions.

…

One of the

impressive things about the above three players is how readily they

embraced collaborations with their counterparts on the continent.

German bass player Peter Kowald's period in London during the summer of

1967 brought him into contact with Parker and soon British musicians

were travelling to the continent to collaborate with Dutch and German

players and the interchange began. One of the earliest combinations to

bear fruit was German pianist Alexander von Schlippenbach's trio with

Parker and German drummer Paul Lovens. Their first recording, Pakistani

Pomade, was done in 1972. Bauhaus Dessau is at least the twelfth

recording by the trio alone (not counting scattered compilation

tracks). Occasionally they would expand to a quartet with the addition

of bassists Kowald or Alan Silva.

That this trio still makes music that sounds this vital and exciting

should be surprising but it isn't. All three players maintain other

group affiliations and when they convene, as in the group above, it's

like an refreshed meeting among old friends. Yet rather than the

conversational approach favored by British improvisers, this group

seems to have a "Jazzier" approach to Free Jazz. Perhaps it's due to

Schlippenbach's piano which draws on the Monk/Taylor tradition, colored

with his own rhythmic and harmonic language. Perhaps it's that as he

has matured, Parker has found a warmer, more Coltrane-like sound on his

tenor which he plays exclusively here. (To be clear, there'd be no

mistaking Parker for Coltrane, however.) Lovens, a seminal drummer in

European Free Jazz (but not as well known as he should be), charges

forth with a barrage of sound that's all clanging metal and thundering

drums. There's usually no grandstanding and each player seems to relish

interacting with his partners. It's just three players coming together

to make music that is uniquely theirs.

Robert Iannapollo, Cadence Magazine, USA, jan-feb-mar 2011

Bill Meyer, Signal to Noise, USA/Kanada, Winter 2011

Obviously comfortable in their own musical skins in an assemblage that

has now been together longer than the Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ),

members of the Schlippenbach Trio are still very capable of finding

fresh and innovative avenues of expression. This CD, recorded in a

Walter Gropius-designed Bauhaus-style auditorium in Dessau, Germany,

confirms this.

Perhaps the reason for the trio's longevity – 40

years and counting – is that unlike the MJQ, it isn't the members'

paramount means of expression. At the very least, with tenor

saxophonist Evan Parker involved in his own trio and electro-acoustic

ensemble; with pianist Alexander Von Schlippenbach with solo work and

Monk's Casino; and with drummer Paul Lovens often working with French

bassist Joëlle Léandre and many others; they have plenty to occupy

their off-time. Plus with the saxophonist in London, the pianist in

Berlin and the drummer residing in Nickelsdorf, Austria they don't even

cross paths that often.

More seriously the band is fully committed to Free Improvisation. So

when the three unite for a tour, not only do they have fresh

perspectives, but also, unlike the MJQ – and despite von

Schlippenbach's name in the title – there's no overbearing music

director as John Lewis was with the MJQ.

That said from its first few notes here, the combo, which has been

recording in this configuration since 1972, is as instantly

identifiable as the MJQ was with exposure to Lewis' piano touch and

Milt Jackson's vibe resonations. More understated beat-wise than the

MJQ's Connie Kay, Lovens uses wood blocks, small cymbals and drop

cloths on drum tops to subdue and vary his rhythm. Von Schlippenbach is

as capable as outputting kinetic note cascades as low frequency

comping, depending on the music's needs. Parker's pressurized breaths,

smears and balanced circular breathing create tones that can be linked

to John Coltrane's or Lester Young's styles in originality and

influence. Plus the absence of a bass player is a non-issue.

Make no mistake about it as well, and Europeanized as it may be, the

Schlippenbach Trio definitely plays Free Jazz. This is especially

notable in the later section of "Bauhaus 2" during the communication

between the saxophonist and the pianist. As Parker's melodic puffs turn

to concentrated glissandi and mouth pops, Von Schlippenbach enhances

his lines with single-note pulses – bringing to mind saxophonist Johnny

Griffin's partnership with pianist Thelonious Monk. Accompanying both

with the restraint Frankie Dunlop or Shadow Wilson brought to Monk's

music, are drumstick-propelled cymbal scratches, press rolls and

wood-block smacks from Lovens.

Developments, variations and interludes are even more prominent on the

CD's almost 41½-minute initial track. With the tempo gradually

increasing and decelerating throughout, texture propelling is the

result of contrasting dynamics, impelled by a combination of cymbal

clatter and rounded ruffs from Lovens; von Schlippenbach's rapid chord

changes, two-handed pummeling and treble clef tinkling; plus Parker's

staccato tongue quivers and broken-octave overblowing. Formalist echoes

of earlier Jazz peek through as well. While the saxman's concentrated

half-squeal, half reed bite may at points reference the New Thing; the

piano player's fortissimo chording sometimes begins to resemble Boogie

Woogie or Stride. Eventually, after percussive key punching from von

Schlippenbach and continuous undulating breaths from Parker, the

saxophonist's shaded reed yelps and bites coupled with the drummer's

rolls and segmented pulse move the piece to adagio from allegro.

Ultimately the pianist's hunting and pecking keyboard shading makes

common caused with the others for a perfectly timed, triple-stopping

finale.

Forty years of playing may mark a record for others. For the

Schlippenbach Trio it's merely a way to create more Free Music

milestones.

Ken Waxman, www.jazzword.com, February 2, 2011

Una caratteristica

importante della maggior parte dei gruppi nella libera improvvisazione

è la brevità della loro esistenza. È forse ovvio che quasi tutte le

collaborazioni casuali, il tipo più comune di raggruppamento nella

libera improvvisazione, tendano a esaurire rapidamente le aree in cui i

componenti provano un reciproco interesse, considerando quindi

soddisfatte le loro comuni ambizioni. Ma anche i gruppi più

soddisfacenti dal punto di vista musicale, sembrano perdere dopo due o

tre anni buona parte della loro vitalità. A quel momento ha luogo un

indurimento delle arterie improvvisative del gruppo; la musica diventa

troppo evidentemente un dialogo, ovvero ha inizio un continuo ricamare

sull'identità del gruppo stesso, difficilmente distinguibile da

un'autoparodia. Qualche volta ha il sopravvento una chiara

autocoscienza, con uno sforzo di semplicità che restringe la musica a

quelli che potrebbero essere o meno i suoi fondamenti. Principalmente,

tuttavia, i gruppi di improvvisazione che hanno suonato insieme troppo

a lungo vanno incontro alla perdita di quello che Leo Smith definisce

il "centro indipendente" dell'improvvisazione, quella parte della

musica che esiste indipendentemente dalle intenzioni di coloro che la

suonano e che sembra provenire da una sorta di relazione di secondo

grado, o subconscia, che si instaura tra i musicisti. L'indefinibile

viene definito e sparisce».

Così Derek Bailey disertando di limiti e libertà ne L'improvvisazione.

Sua natura e pratica in musica. Era il 1980, e il trio

Schlippenbach-Parker-Lovens stava già in pista (per lo meno) da otto

anni: dal novembre del '72, data di registrazione di Pakistani Pomade,

opera prima uscita su FMP e ristampata poi dalla Atavistic.

A dividere il novembre del '72 da quello del 2009, nel cui diciottesimo

giorno è stato registrato, dal vivo, "Bauhaus Dessau", di anni ce ne

sono invece la bellezza di trentasette. Che se ci si pone nell'ottica

del Bailey pensiero equivalgono a un'era geologica. Eppure il "centro

indipendente" del trio Schlippenbach-Parker-Lovens ancora c'è e ancora

pulsa. Il fluire dell'improvvisazione, concerto dopo concerto, disco

dopo disco, non ha perduto nulla in quanto a urgenza e tensione

creativa. Il relazionarsi di pianoforte, sax tenore e batteria continua

a essere basato sulla creazione-esplorazione di nuovi spazi, sul

generarsi e rigenerarsi delle dinamiche, sul ripensare i limiti del

possibile, sull'andare oltre l'acquisito evitando che la consuetudine

diventi menomazione. Anzi, proprio partendo dall'esperienza comune e

dalla reciproca familiarità, che inevitabilmente seguono una parabola

di lento ma costante accrescimento, il trio riesce sempre e comunque a

raggiungere un altrove. Non aspettando che qualcosa accada a livello di

relazioni secondarie, subconscie, ma facendo accadere quel qualcosa

intenzionalmente. Una questione di faticosa volontà. Coscienza. Anzi,

autocoscienza. Frutto di rigore e dedizione totale, analisi e

autoanalisi.

«Le cose di cui si dà per scontata la conoscenza formano probabilmente

un contesto utile come nessun altro per lo sviluppo di nuovi aspetti».

Così rispondeva lo stesso Evan Parker agli argomenti di Derek Bailey

nel saggio citato qualche riga sopra. E ancora: «La gente con cui ho

suonato più a lungo è quella che in pratica mi offre la situazione di

lavoro con la libertà maggiore».

Limiti e libertà (per tre). O meglio: libertà (per tre) senza limiti.

Valutazione: 4 stelle

Luca Canini, italia.allaboutjazz.com, Italia, 09-05-2011

British saxophonist Evan Parker is just a few years away from his Jubilee Celebration as his country's most celebrated jazz export. What has contributed to such remarkable longevity - particularly considering he inhabits the punishing avant garde sphere - is that he has been international in scope and omnivorous in style since almost the very beginning. He's a founding father or elder statesman in theory; in practice, he plays with the same curiosity as he did at the outset. His most stable outlet has been in a trio led by pianist Alexander von Schlippenbach with drummer Paul Lovens. Bauhaus Dessau, named for the German art center where this 2009 concert took place, is the latest in a mini-flurry of releases since 2003 by the group, which has existed for over 40 years, making it one of the longest-standing free-improvising ensembles in history. Few marriages last as long. And like a successful marriage, there is a delicate balance between knowing someone more than intimately and still being surprised by them. The three tracks, in descending lengths of 41, 12 and 9 minutes, featuring Parker solely on hefty tenor, both capture a particularly fine moment and represent a blip in their trajectory, a strange tension between history and ephemerality percolating with each moment.

Andrey Henkin, THE NEW YORK CITY JAZZ RECORD, USA, June 2011

Chris Searle, Morning Star, Great Britain, November 22 2011

Se è vero che non è immortale il contingente, è anche necessariamente vero che la sua vitalità si esplica nell'essenza dell'espressione, naturale senza artifici, intrinseca non esterna, costantemente in divenire e dunque presente in quanto temporalmente assente, sfuggevole, sempre in itinere e mai al punto di arrivo.

Alexander von Schlippenbach (pianoforte), Evan Parker (sax) e Paul Lovens (percussioni) in trio, al Bauhaus Dessau, celebrano quarant'anni di musica insieme, ed è l'improvvisazione immanentemente incostante che balugina irriducibilmente, a renderli tanto uniti.

Note trasversali dal pianeta del free, come ci presenta la stazione Intakt, ormai proverbialmente orbitante in una costellazione discografica pressoché da primato. Free percepito e razionale e al contempo fugace e asimmetrico, messo in opera da veterani che sanno fronteggiare i propri alter ego strumentali, mossi da menti e dita certamente non intorpidite e senza velature di cali creativi. Improvvisazione sintomatica, prepotentemente allegorica e tuttavia primitiva e disadorna, poiché svanente e inafferrabile come le verità preistoriche. L'abbattimento delle barriere non equivale alla distruzione dei legami, bensì vuol rappresentare, o meglio, "sente di essere" quindi è, creatività stravolgente, sovversiva, che tuttavia dista anni luce dall'anarchia sensoriale, ponendosi come scoperta di terre nuove o immersione nei mari dell'inconscio, ignoti e temuti ma non per questo da non conoscere o da paventare aprioristicamente. La narrazione musicale è alterata e alterante, riverbera su chi ascolta come novità nella novità, rimanendo fedele al principio dell'infedeltà che è proprio dell'istantaneo.

Il punto nevralgico della creatività è molteplice e, come energico logos, si dirama per le indeterminate vie dell'invenzione, non unilaterale (poiché negherebbe se stessa), bensì multiforme e in movimento proprio come i quaranta minuti del disco che, liberi e aleggianti, nonché vulnerabili, procedono con indisciplinata grazia, erompendo in non-unisone e contraddittorie forze.

Jessica Di Bona, Jazzconvention, Italia, Martedì 18 Dicembre 2012

|