There is an elusive but audible unity to German alto saxophonist/clarinetist Silke Eberhard. Her approach inhabits a universe equal parts exotic and playful, as if the seriousness pervading it was simultaneously on the point of being dispelled. Each ensemble also speaks to that dualistic unity, referencing Eberhard's musical past as it intersects with the historical narratives she has done so much to champion.

A greatly expanded Potsa Lotsa ensemble, the group that committed Eberhard's expertly conceived and executed Eric Dolphy projects to disc beginning more than a decade ago, is joined by Korean gayageum (plucked zither) virtuoso Youjin Sung on Gaya. Its five pieces, named for the first five Korean numbers, demonstrate the Dolphy-esque whimsy is still present but somehow both expanded and deliciously distilled.

The third piece lopes forward with a grandeur soon usurped by episodic jollity in the service of kaleidoscopic sound straddling various cultural lines in joyful recalibration. The second piece enters life with similarly fanciful gusto, gayageum in a setting conjoining blues and chamber music but with Taiko Saito's muted vibraphone and piano innards plucked for all they are worth (courtesy of Antonis Anissegos) as quiet brass surfaces like minnows over a vast ocean of pointillistic and Protean harmony. The album's cyclic conclusion reintroduces the grandeur, allowing the various comic interludes a context of depth and maturity.

In contrast to the luxuriously jasmine-scented flavors emanating from the enlarged Potsa Lotsa project, the Takatsuki Trio Quartett's At Kühlspot dives deep into Eberhard's diverse improvisations in a very different context. At 9:53 and beyond in this single-track album, her daredevil interregistral leaps doff the hat toward the quasi-theatrical irreverent fun of Charles Mingus and even toward those not usually associated with such lightheartedness, like the similarly inclusive freedoms of Jimmy Lyons. The unusual combination of Antti Virtaranta's acoustic bass and Joshua Weitzel's shamisen complement Rieko Okuda's especially brassy piano, punching Monk-ishly through the layers of rhythmic intricacy. A word about Okuda's pianism: her penchant for unique contrapuntal textures complements the melodic intrigue of Eberhard's playing, bringing a bit of chamber music to a hard-edged session. Okuda's vocalizations raise the ante by introducing a linguistic layer, again referencing syntaxes unknown but almost and elementally familiar as the marshes, flats and hill-and-dale juxtapositions roll on.

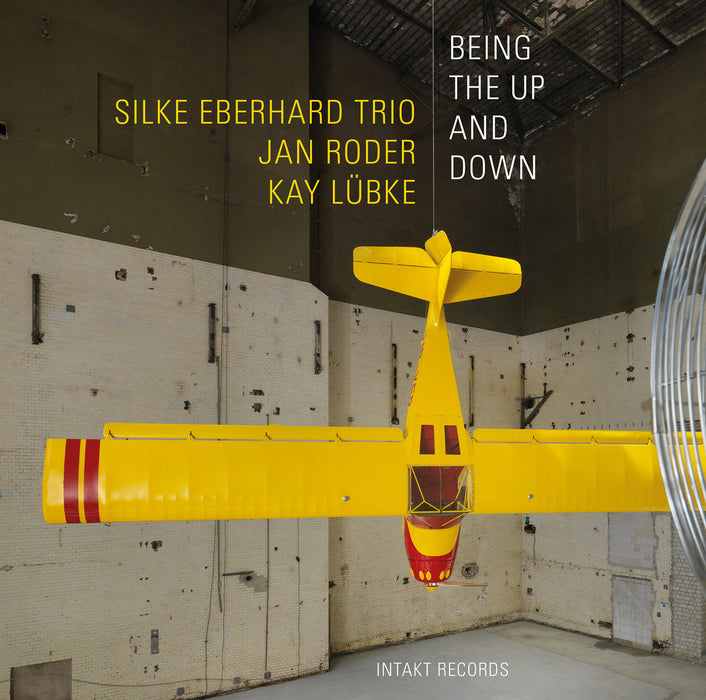

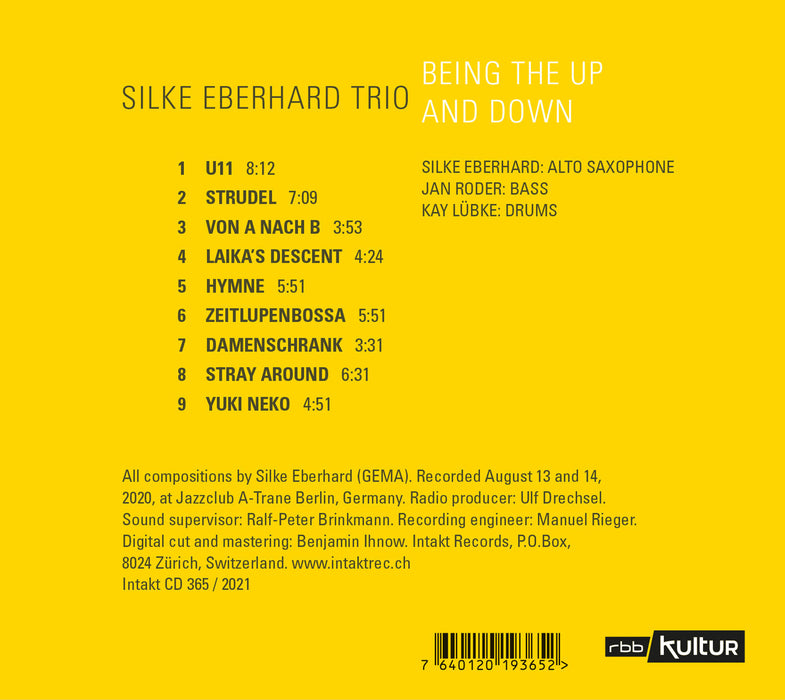

Being The Up and Down, the newest offering from Eberhard's trio, affords the best of both previously described worlds. Only dig into the serenely unisoned opening of "Zeitlupenbossa" to be transported east again in a haze of rapturously rolled and sustained percussion seasoned with bass harmonics. That vibe continues as Eberhard's gorgeously serpentine melody is supported by drummer Kay Lübke's delicate brushwork and bassist Jan Roder's slow walk and droning repetitions. All is spacious implication and dreamy interaction in the ballad world. Not so with the spasmodic whiplash and laugh-out-loud sarcastic wit of "Strudel". Lübke and Roder's swing and stamina are both wondrous to behold as Eberhard sails through register and timbre shifts with ease, blasting those oft-cited improvisation and composition boundaries to smithereens. The mix of studio and concert performances is so tastefully done that the obviously

'live' drum solo in "Laika's Descent" may lead the listener to anticipate applause at track's end, to no avail. Beyond all allusion and synthesis,

as

with every ensemble hosting this extraordinary performer and composer, Eberhard's trio blends familiarity and novelty with the stunning clarity of a veteran who has never lost the innocence of pure enjoyment through exploration.